Richard Serra, Sea Level (1996)

Flevoland, Netherlands

June, 2025

Background

This is the first post of five Land Art Flevoland sites that we visited in June, 2025. (I’ll repeat the next two paragraphs for all five posts, it is the same as the original series of the other five we’ve visited)

Flevoland is the twelfth and newest province of the Netherlands. It exists in the Zuiderzee / Lake IJssel (a shallow bay connected to the North Sea, which they somehow converted from a body of saltwater into fresh water now), and almost the entirety of the province was added in mainly two separate land reclamation projects or polders. The first was in 1942 and the larger second started in 1955 and was completed in 1968. Flevopolder (as this new island was called) is the world’s largest artificial island at around 1,500 square kilometers.

Land Art was in its hayday of the 1960s and 1970s. In conjunction with the opening of this new land, the planners decided to add some land art pieces to become a part of Flevoland. Thematically it makes a ton of sense. Both creating Land Art and the empoldering process share a strong connection to the Earth and transformation of the landscape. You could even say that reclaiming this island was an even grander land art project. They’ve added 10 land art pieces now, with the most recent being completed in 2018.

Sea Level by Richard Serra is a sculpture located in Zeewolde, the Netherlands, created in 1996. Composed of two long, weathered concrete walls embedded into the polder landscape, the work’s height is the actual elevation of sea level, contrasting dramatically with the land around it, which lies several meters below. As visitors walk through the piece, the walls rise and fall relative to the surroundings, offering a physical and visual reminder of the Netherlands’ reclaimed geography and human relationship to natural forces.

Each of the two concrete walls are 200 meters long, with the gap between them also 200 meters long (making the total line 600 meters long). The gap also features a bridge connecting the two sides of this canal. The reinforced concrete is about 25 cm thick. It is very difficult to view the entire line together, the best vantage point is from the central bridge or near it, and try and pan around to see the entirety. From either end, the bridge interferes. The bridge seems to predate the piece, which is unfortunate. It would have been cooler to be able to stand on one end and see all the way across to the other, but alas, Serra had to build it using the existing environment.

You can walk along the sides of it on either side or either wall, though the main path is on the western side of the canal. Graffiti was common on it, but it was recently restored in 2024 to remove graffiti and they added a protective paint to try and prevent more.

It reminds me of Double Negative, with a negative space in the center, that you have to imagine to fully appreciate.

A panorama view from the western third of the sea level line.

Travel

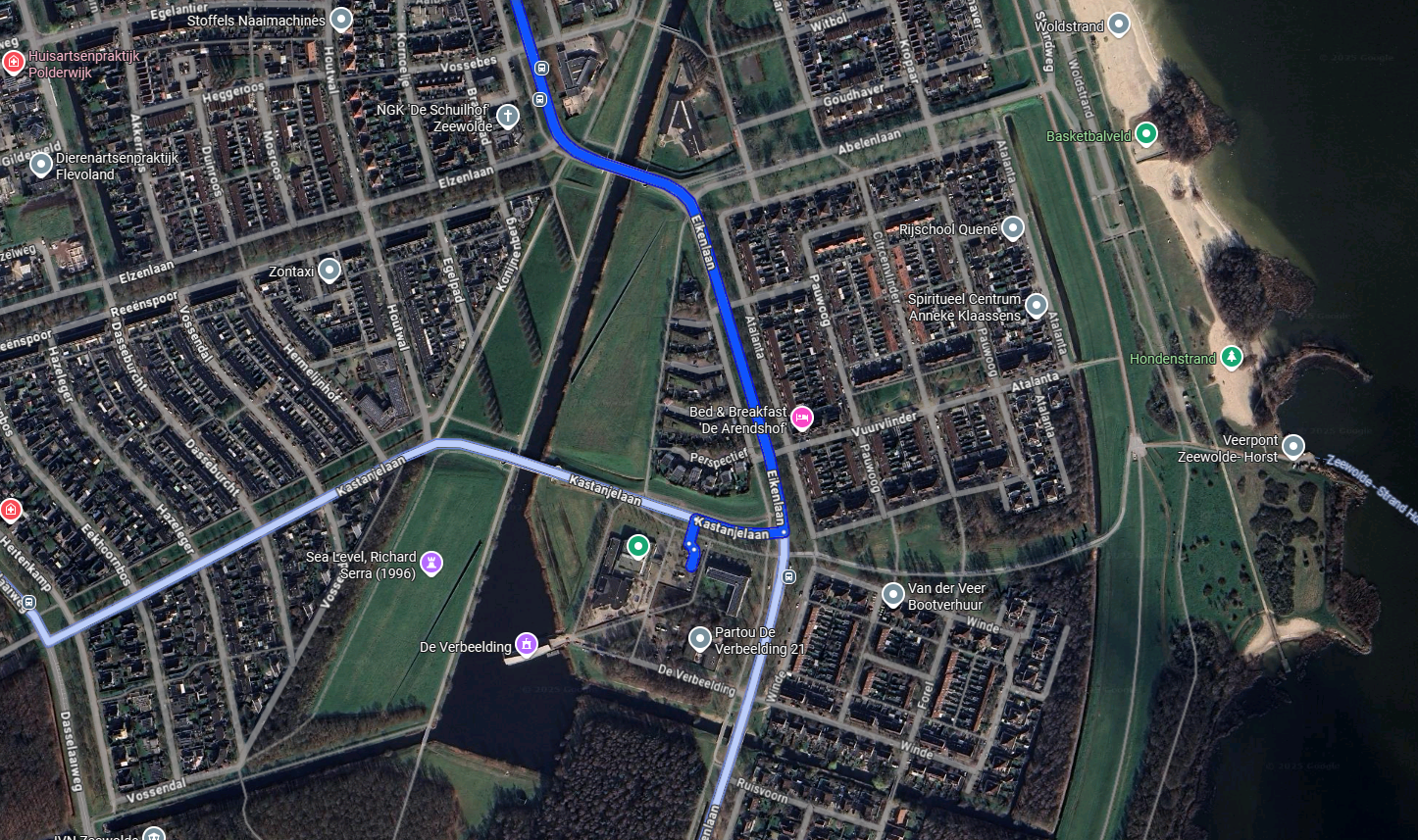

It is about a 45 minute drive from Amsterdam. It is only accessible by car, although I suppose if you found your way via public transportation to the town of Zeewolde, it’s small enough that you could walk over.

Zeewolde is off of the N705, which itself is off of the N305. There’s a convenient public and free parking lot located at the Sportzaal Zeewolderhoek. From there you can walk along the entirety of the public park and art piece. I would suggest that for your navigation as just putting in Sea Level may send you just to a nearby road by the park. There is definitely some street parking available, but the lot is just easier. There are obvious paths along the edges of the park as well as desire paths alongside both walls, some areas are more trodden than others, but certainly plenty. I would suggest wearing closed toe shoes dependent on the weather. It was certainly wet and a bit muddy when we were there.

There were no public available facilities that we could see. I’m sure if you looked around town there would be some accessible restaurants and bathrooms around Zeewolde. This building De Verbeelding on the water seems to be a possible building to check out, but it looked empty and closed when we were there. Sea Level and the public park are free with no hours of operation. There are no lights, so I would stick to daylight hours. But it’s within a highly residential area so I’m sure it’s pretty safe regardless of time of day. There is also a monument to American and British pilots who crash landed and died in the area (photo to the right) (though at the time it was just water). It also has one of the few Land Art Flevoland signage plaques that is still in good condition.

Nearby is a public beach as well, we didn’t visit it because it was slightly raining while we were there.

Experience

This was our first stop of our wet June day, arriving at around 11:00. We were the only people there (other than those just walking along the riverbank) for the hour we wandered the installation and ate lunch. There was a light intermittent drizzle, and definitely made the ground a bit soggy. While it’s basically all flat and trodden, I would suggest closed toed shoes. It is accessible to anyone who wants to walk alongside it / around it. We ate grocery store packed lunch out of the back of the car.

This is about the midpoint, the canal and bridge cut right through the negative 200 meter space in the center. You can’t really see Sea Level on either side, but it’s there. I find this negative space really ruined by this bridge, but the art must exist within a public space, and better it be utilized and accessible than just for art’s sake.

Summary

This is a cool piece, but isn’t particularly impressive enough to warrant a trip out here. Nor is it one of Serra’s more interesting pieces. I do really like it in juxtaposition to Double Negative, but it falls short in terms of a memorable experience.

If you want to see how it stacks up against the rest of Land Art Flevoland, check out this tier chart.

Podcast / Interview

This is a link to Land Art Flevoland’s podcast / interview about Sea Level. It is unfortunately in Dutch only. But I did put it through a transcriber (notta) and translator (Google). I apologize to the original content creators, I had to edit and bridge some gaps, but hey, I don’t speak Dutch, and I just wanted to share their content with more people. Hopefully they don’t mind. Below is the badly transcribed, translated to English, and edited interview transcript.

Luke Heezen: Sea Level is a 1996 artwork by one of the greats of landscape art, the American Richard Serra. He had two concrete walls placed, each 200 meters long, in a straight line, but interrupted by a space of 200 meters and a canal that runs between them. The walls are included in the lowest part of Landschapspark de Wetering in Zeewolde and are exactly as high as the sea level. Walking along the walls you physically experience how high the water would be if we had not built dikes. Probably a simple demonstration, but one that precisely addresses the essence of Flevoland.

Opposite me sits Demelza van der Maas. Expert in museums and heritage, she obtained her doctorate on the formation of heritage and identity of the IJsselmeerpolders. And she is also chairman of the board of the county of Flevoland. Welcome.

Demelza van der Maas: Thank you.

Luke: I call it a simple demonstration, very symbolic. Is that also the way it is looked at here in Zeewolde and how it is appreciated?

Demelza: It has not always been appreciated. If you go back in history and want to investigate when Sea Level was actually made and with what intention, you have to go back to the eighties. Then there was an association, a religious, socialist movement, the Woetbroeders. They wanted to build an education center here in the forests near Zeewolde, where you could follow courses. The idea was that there would be an art route that would connect that center with the center of Zeewolde. That had to be an art route that would have a popular uplifting effect. The people who would walk here in that area would learn something from it. That Woetbroeders Centrum never came, but the municipality was very enthusiastic about that idea of an art route here in Zeewolde. They embraced that, just like the Rijksdienst voor de IJsselmeerpolders. They gave orders to have a concept made for that. That was done by Bas Maters in 1985 already. And that is actually where this landscape park de wetering was designed. And right from the start the idea was that there should also be a large supporting artwork. And that artwork eventually became Sea Level. Richard Serra already got the assignments to make that design in 1989. But it took until 1996 before it would come. Because all those ideals soon came into conflict with the reality of politics. Money had a lot to do with it. It was a very expensive work of art to make. And that idea of what is popular actually clashed a bit with the pragmatism that has always prevailed here in the polder. Well, eventually it came. But you see that the artwork was not immediately embraced. Despite all the ideals, people found it complicated. It is simple, of course, but at the same time very compelling. Because you can't really get around it. You have to adapt your movements to the artwork. And not everyone was happy with that.

Luke: And the stories around it, because you could say that is exactly what this place stands for, what this province stands for, that is almost about your own DNA as residents or is that something that is perhaps formulated too mythically.

Demelza: Yes, in my research I did research on the stories that are told here in the polder about the past. Those pioneers, those people come here to build something new without the burden of the past, that is very prominent and certainly in art. It was also one of the basic principles of the imagination, as this landscape park would eventually be called, or the art initiative around it. How pioneering shaped the people here. And of course you can see that in the art that was eventually put there. But for a lot of people, that's very abstractly represented here. It's minimalistic. Richard Serra is also known as a kind of master minimalist trying to achieve maximum effect with minimal means. But for many people it is still a bit too abstract.

Luke: Yes, that's funny of course with landscape art, you have to want to surrender to that too, you have to see it in it too, you have to find it interesting to go through the thought experiment behind it. What is interesting in that context is that there is now another monument or another work here, at least, an object that is perhaps 100 metres away, a large memorial to the Allied pilots who crashed during the Second World War when it was still the Zuiderzee. A large metal wall of at least 2 meters high, the recess of an airplane propeller and, lest we forget, in large letters.

Demelza: Yeah.

Luke: There hasn't been that much protest about it, what difference do you think it would make?

Demelza: The difference lies in two things, the Richard Serra and also the works of art that were subsequently realized in and around this landscape park, were really at the initiative of governments and art professionals, so people who know how it should be done, who understand art and who also select famous artists, who are internationally renowned, to make a statement here. The monument you are referring to is actually a completely what you would call a bottom-up initiative, so it came from the initiative of a local person, an aviation historian, who felt that it was time to pay attention to the victims who fell during the Second World War pilots, who crashed in the IJsselmeer area, after bombing Germany among other things and who died here, who also raised money for this via crowdfunding, the artwork was designed by a landscape architect and design agency from Zeewolde, it was also made locally here, so it was actually entirely conceived and therefore also supported by the local population, who now have a place to come to that they themselves conceived and designed and in that respect it enters into a very interesting conversation with the Richard Serra, where it was very much about ideal and elevation, but which clashed greatly with what people actually wanted locally and on the other hand there is a monument that was completely conceived, made and realized by the local population and therefore has actually been supported right from the start, so that is a very interesting dialogue that is taking place here in the park now.

Luke: Yes, and yet it is also interesting to see, because there is now an action hashtag, what is this doing here? What does it actually require from reactions of residents or people who often pass by? What do you think of this work and how is it embedded in your life? And then Serra also comes forward positively, there are also positive stories around that. Maybe you could also say that such a landscape work has to grow, has to become undone in that given.

Demelza: Yes, I think it certainly makes sense to say that. In the meantime, the work has of course been around for twenty-five years, the Serra, the Sea Level. So it has had time to settle in the environment, people have adapted their movements to it. They encounter it every day when they walk the dog. They may have had a picnic or a birthday party there. So new memories are created around it. And what you also see, for example through the Land Art weekend, which we are of course in the middle of now, is that all kinds of activities are organized. New performances, sometimes by local theatre associations or artists from the area. And they enter into discussions with such a work of art. And then you see that a new layer of meaning actually arises on top of the original intention of the artist. And I think the more that happens and the more people participate in it, or at least experience, that the work can have many meanings depending on how you relate to it, that it slowly starts to find a place in the community. I think if you had tried this hashtag maybe twenty or fifteen years ago, you would have gotten a very different response. And maybe that's just the aging process.

Luke: Yes exactly, then you can grow with it again and the bond of it, that just has to arise, that has to grow.

Demelza: It is very interesting to see how the reactions you get now compare to the reactions that were there around Kunstreact de Verbeelding, around the year 2004. At that time, there was a really aggressive reaction to the artworks, then real vandalism was committed. In that sense, art did what it had to do, namely it entered into a dialogue. Only the effect was more intense than the artists and initiators of this project had anticipated. And that is also the reason why the project was eventually stopped. And if you now look at what is happening around the artwork and how it has actually found a place, then you see that time has indeed done a lot. And perhaps the climate too, a little.

Luke: Yeah. You are now chairman of the board of Leus from Flevoland. Do you take this knowledge, because that is what you may call it for the knowledge of how public art actually works and how it becomes a bond. Do you also take that into account in how you approach it so as not to end up in the same trajectories as around an imagination?

Demelza: Yes, definitely. What you see is that it is also increasingly becoming a focus for the provincial and municipal governments. When an assignment is put out, they not only think about commissioning a new artwork but also about how to create public support from the very early stages. With people who live in the province or municipality where the artwork is to be realized. This can sometimes be done by organized consultation moments. Or by specifically giving the artist a task in his design process of, where does the conversation start? With people who live in the area, how do they use the space? What are the things that they encounter there? What are their goals? And in that way you can of course do much more with, what we call, the genius loci, the spirit of the place, to incorporate that in your artwork. So you also see that it is often an ongoing process. And things like Land Art Live, where performances are organized at works of art that are already there, they also play a very important role in it. Because you can put the artwork down and assume that it is finished, but actually, that’s only when it begins. At that moment it comes to life and you can, as I just said, try to add those layers of meaning.

Luke: We're actually going to go through all of those works this weekend with an extra story and we'll also talk about their operation. What do you think a good landscape artwork should do, ideally?

Demelza: Yes, then I go back a little to the original idea, also what was behind the imagination. Because that is challenging. So that it challenges you to look at an environment in a new way that you think you know. By adding something to it or by creating movement in whatever way. And by stimulating your senses. And there are places like “twisted horizon” (?) for example. Where you stand at the edge of the water, feel the wind in your hair, smell the water and at the same time see the waves moving. That is a place where you are challenged and stimulated in all sorts of ways. And that is actually the same here at Richard Serra. In my experience, when I stand next to that wall, I feel a bit of the cold of the concrete. That feeling of the water gives. You get a little overwhelmed when you walk along that wall. For me that is the essence of landscape art. That you are really challenged to look at your surroundings in a new way.

Luke: Yes, and also physically, right?

Demelza: Very physically, yes.

Luke: So not just looking at that wall, but standing next to it, feeling it, walking past it.

Demelza: Yes, really the sensory aspect of it, which you are never allowed to do in a museum. The touching, many people still tend to stand just a little too close to such a work of art. Here that is allowed, you are allowed to walk over it, you are allowed to walk through it. You can touch it, smell it, feel it and that is what makes landscape art special.

Luke: Yes, so it is there, it is for everyone and make your own story, make sure you have a connection with it yourself. Or not, you don't have to like it of course, but make sure you don't do anything more.

Demelza: Yes, it certainly carries a risk and that is also the risk that has clearly been experienced here. If it is at the moment that you invite people to interact, then that interaction can also turn out differently than you might want. Because people bring their personal baggage to such a work of art. And have associations that you might not expect and that also makes it exciting.

Luke: So maybe we should say, keep the work whole, but still connect with it.

Demelza: That's a good disclaimer.

Luke: Okay, thank you, folks.

Sources

https://landartflevoland.nl/kunstwerken/richard-serra-sea-level-1996/